Authored by: Ms. Lilies Njanga, Africa Director, Malaria No More

Malaria is a disease that still takes a child’s life every two minutes. It is underfunded and deprioritised and costs the African economy almost $117 billion in productivity losses a year, yet it is cheaply preventable and treatable. It is a disease that this generation can end, but only if we act now.

Decisions made now by political leaders globally – backed by strong private sector support – will determine this trajectory.

Malaria continues to take a disastrous financial toll on the African economy, denting country health budgets with huge amounts spent on malaria control and treatment, and resulting in an average annual reduction of 1.3 per cent of Africa’s total economic growth.

The last two decades have seen some transformative progress against malaria, with interventions saving 10.6 million lives and preventing 1.7 billion cases – but malaria is fighting back, and cases and deaths rose to the highest number in nearly a decade in 2020. Whilst the on-going COVID-19 pandemic has made the fight against malaria even harder, contributing to a 12 per cent increase in malaria deaths, years of plateaued global investment and faltering political will have all contributed to concerning signs of malaria resurgence.

The African continent as whole accounts for 95 per cent of all malaria cases and 96 per cent of deaths. The World Health Organisation (WHO) reported a staggering 627,000 malaria related fatalities in 2020, of which 10,700 were recorded in Kenya. Sadly, African children still bear the brunt of this disease, with close to half a million children under five losing their lives in 2020.

Annually in Kenya, there are an estimated 3.5 million cases diagnosed, of which children constitute 67 per cent. The heavy human cost of malaria can be measured in each and every life lost, and the many, many, more lives that are diminished. High case numbers continue to result in financial burden putting a strain on resources necessary to achieve universal health coverage. Yet the cost of malaria goes far beyond health budgets, costing the African economy almost $117 billion in productivity loses per year. For many families, malaria also threatens individual economic livelihoods, with children regularly absent from school and parents unable to work. Many Africans living in rural areas survive on less than $1.5 a day, trapping the most vulnerable in a vicious cycle of sickness and poverty, with little opportunity to escape.

Unfortunately, today approximately 70 per cent of Kenyans are still at risk of contracting malaria, with only 40 per cent of households owning at least one long-lasting insecticide treated net. In Kenya alone, approximately 170 million working days and 11 per cent of primary school days are lost every single year, with malaria accounting for 18 per cent of all outpatient visits and 15 per cent of all hospital and clinic admissions.

Taking positive steps to mitigate the malaria burden, the primary goal of Kenya’s current national malaria strategy is to reduce malaria incidence and deaths by at least 75 per cent of 2016 levels by the end of 2023.

Although the country is not on track to hit the WHO’s Global Technical Strategy (GTS) targets at present, in no small part due to the impact of COVID-19, continued efforts have ensured that the country has sustained reductions in case incidence, with the burden dropping the prevalence rate from 8 per cent to 6 per cent in 2020.Despite this notable progress it important to note malaria is among the top five causes of death for children under 5 years of age.

The WHO has warned that Kenya’s malaria funding allocation is too low, significantly impeding progress in the malaria fight, although this is not a challenge faced by Kenya alone. Year-on-year the WHO has reiterated that a lack of significant domestic funding, as well as international funding, is still a key factor limiting malaria control in many countries, with current malaria investments falling $3.5 billion short of the financing needed to extend the global coverage of insecticide-treated nets and prevention and treatment drugs.

But there is hope!

Learnings from previously successful national malaria control programs in China and El Salvador indicate that newly malaria-free economies experienced higher economic growth and are capable of developing industries previously weakened by their malaria endemic status. Modelling suggests that while the costs of eradicating malaria globally could be $90- $120 billion between 2015 and 2040, the economic benefits are estimated to reach $2 trillion between 2015 and 2040, as a result of huge productivity gains and health savings.

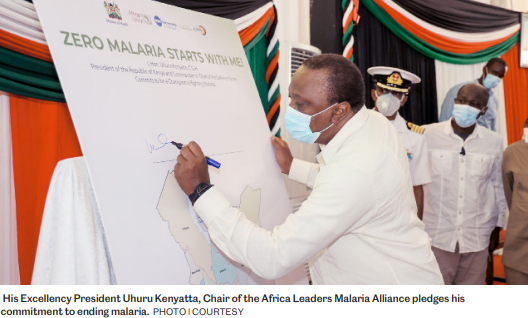

When businesses take the lead in the fight against malaria, their workforce is significantly healthier, leading to more reliable and motivated staff, and a positive impact on overall profitability. Indeed, the private sector is a critical partner for the Kenyan government, and one that can complement the Division of the National Malaria Programme (DNMP). Private sector businesses have the power to positively influence and encourage leaders to take urgent action against this deadly disease. With a significant and sustained boost in support from the private sector and private philanthropists Kenya can make a quantum leap, leveraging the goodwill from H.E President Uhuru Kenyatta in his capacity as chairperson of the Africa Leaders Malaria Alliance (ALMA) and the recent launch of his administration’s Malaria Youth Army.

Innovative private sector investments in prevention, treatment measures and equitable access to lifesaving commodities will not only help to break the disease-poverty cycle but will ensure a more sustainable and prosperous future for Kenya, particularly in hard to reach and vulnerable communities. The Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI), for example, recently launched the first locally developed malaria diagnostic toolkit, representing a great step towards developing home-grown and affordable malaria solutions. There is still a need to invest in local manufacturing of commodities such malaria medicines and long-lasting insecticide treated nets to help facilitate better access at the community level, but progress is now being made.

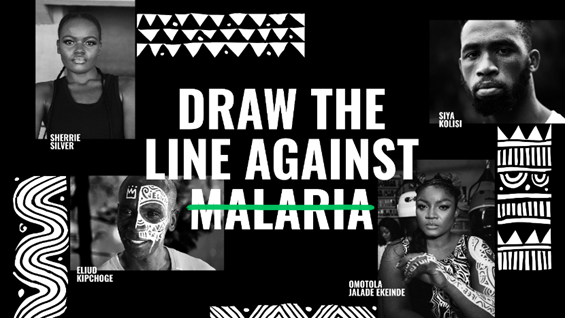

Africa has the youngest population in the world, with 76 per cent of those living in Sub-Saharan Africa aged under 35. While this demographic is most impacted by malaria, more importantly, they have the unique ability to create change and be the generation to end this deadly disease for good. As far from the East to the West and the North to the South of Africa, young people have been uniting in their ambition to beat one of the world’s oldest diseases through Zero Malaria’s Draw the Line Against Malaria campaign. This fight against malaria needs concerted efforts, including from the private sector, in supporting such campaigns to advance and amplify young voices as they call on leaders to renew their commitments to ending this deadly disease within a generation.

Africa has the youngest population in the world, with 76 per cent of those living in Sub-Saharan Africa aged under 35. While this demographic is most impacted by malaria, more importantly, they have the unique ability to create change and be the generation to end this deadly disease for good. As far from the East to the West and the North to the South of Africa, young people have been uniting in their ambition to beat one of the world’s oldest diseases through Zero Malaria’s Draw the Line Against Malaria campaign. This fight against malaria needs concerted efforts, including from the private sector, in supporting such campaigns to advance and amplify young voices as they call on leaders to renew their commitments to ending this deadly disease within a generation.

As long as malaria exists it will continue to act as a chronic engine of poverty and inequality. We have the tools and knowledge to end this disease and by scaling up private sector business support in conjunction with improving and expanding national infrastructure, this is undoubtedly a fight we can win. The support of private sector businesses and private philanthropists has never been more vital.

Contact Information

Ms. Jenny Njuki

On behalf of the Kenya Zero Malaria Campaign Coalition

Email: [email protected]